(Twitter, 2023-06-09)

Some days ago, Apple released their new VR glasses named „VisionPro“ and reactions on Twitter already indicated that a new (old) hype might be approaching: „Will technology transform …“, could this „lead to the end of civilization?“. Really? Do we want to, again, discuss the potentials, risks, and limitations of a MetaVerse or a PokemonGo agumented reality? Or, can we just acknowledge – and this is my claim – that people share such fantastic stories out of excitement but without promising or expecting them to come true? However, if so – Can we ignore these stories or should we care if they motivate and mislead action?

Okay, you might say that this claim is not at all revolutionary. But what intrigues me is how stories disseminate, allow learning, and motivate action – even when people consider them just funny but not realistic.

In the social sciences (& STS), there are many great studies about the roles and impact of the imagined future on technology development. People study how visions motivate action and investments, how guiding images help coordinate interdisciplinary projects or aid to communicate science and deliberate about risks, and generally suit for learning or planning. The most prominent theories are the sociology of expectations, sociotechnical / social imaginaries, projective grammars, and Vision Assessment. As scholars share an interest in how present futures impact the present, it makes sense to form a community and, for the sake of inculsion, to be not too strikt about the use and meaning of regarding concepts. However, when we aim to assess hype communication or intervene in visionary practices, we must be more certain about intentions: What is to be imagined and what is to be believed about the future?

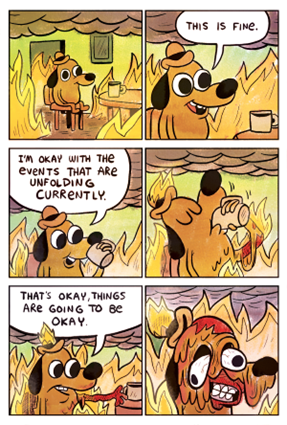

The difference becomes obvious when I ask you to imagine that your house is on fire and when I ask you to believe that your house is on fire. First, you can only voluntarily imagine but not believe that your house is on fire. Second, you can imagine that your house is on fire without feeling the urge to act while „this is fine“ would be an inappropriate reaction (see the „this is fine“ comic on the right). Third, both imagining and believing can cause an emotional reaction. And – and this is where it gets interesting – we can learn from „imagining under constraints“ (Kind 2016), when we colligate beliefs in a „creative“ way that allows for inferences. For example, we can imagine that our house is on fire while looking at a emergency map to find out what would be the fastest exit route. This means, we come to believe something about our environment and there is no reason to believe that this will not be true in a possible future.

In her chapter „Imagining Under Constraints“, Amy Kind explains how we can learn from inferences of beliefs and how our learning can be misled by „imaginative illusions“. She therefore distinguishes „change constraints“ and „reality constraints.“ As with a science fiction story, you “set up a basic proposition — then develop its consistent, logical consequences.” (Campbell 1966 in Amy Kind 2016). In the aforementioned example, we might wrongly constrain our imagination with an outdated map and, therefore, falsely belief what is a good exit route. Or we derive false conclusions because we missed to also consider how smoke and heat spread in the building. Assessing what we should or should not imagine, however, is a different debate which I would like to refrain from in this short blogpost.

Comming back to our terminology: Expecting means to believe or desire that something will be the case. Promising means to license others to use our commitment as a premise in their reasoning. Both, the promise and the expectation that our house will be on fire, are not prerequisites for learning about the fastest exit route. Still imaging the scenario leads to new beliefs and our actions are sensitive to beliefs. Therefore, we should not only empirically observe and critique what people believe about the future but also what people imagine. And as communicators, we should make clear to our audiences what is to be imagined and waht is to be believed. Next, we should also consider 2nd order expectations. One might believe that this „extinction story“ is worth telling, that this ironic *pretense* will make the technology more popular and that the expected attention motivates naive investors („greater fool theory“). And still, imaginging that VisionPro could lead to the end of civilization is different to believing the consequences of climate change, as we can say with Greta Thunberg: „I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if our house is on fire. Because it is.“ – according to what we know about our reality.

This is the end.